Over the past 15 years, we’ve dropped the hook all over New England and spent three winters in the Caribbean, anchoring hundreds of nights in all sorts of conditions. Along the way, we’ve learned (sometimes the hard way) what works, what doesn’t, and what really matters when it comes to anchoring.

If you’re new to anchoring or just want to tighten up your technique, here are some tried-and-true tips we live by. The goal is to anchor like you wish everyone upwind from you would. Let’s drop the hook…

Approach Upwind—Always

This one seems obvious, and yet we continue to see all kinds of creative variations on this one. When preparing to drop the anchor, always approach into the wind. This ensures your boat will come to a stop and fall back naturally, and the rode will lay out properly.

Approaching from crosswind or downwind is asking for trouble. You run the risk of fouling the chain under your boat and not having the anchor set in the proper orientation for the wind. It also confuses your new neighbors.

Be a Good Neighbor

It takes some practice determining the best place to drop in a crowded anchorage. Ideally, you don’t want to end up too close to anyone and you certainly do not want to foul your anchor with anyone else. Know the wind forecast – if you stay any length of time, chances are the wind will shift. The Trawler upwind from you will be along side later. The boat next to you will be ahead of or behind you.

If you find yourself next to another boat and fairly close to it, that’s a potential problem. If the wind shifts much, you may find yourself in a very cozy situation – a Gray Poupon moment if you will. Don’t worry about who got there first. If the other boat won’t move and a wind shift is coming, you might consider moving yourself.

Try as you might to not end up on top of someone else’s anchor, it happens – especially when the boats swing with wind shifts. In reality, it’s not usually a problem for a boat to weigh their anchor if another boat is directly above it. In any case, if after paying out your rode, you are not happy with where you are sitting with respect to your neighbors – just do it again. Easier to do it now in the daylight than it 2AM when you are getting really close to someone.

Keep the noise down! Besides saving money, lots of people like to anchor for peace and quiet. Party-time day anchorages aside, try to observe some peaceful time at night and in the morning. Plan your generator time accordingly. And we thank you.

Ground Tackle

“What’s the best Anchor?” will start a fight almost as fast as “iPhone or Android”?. (of course, Android is the correct answer).

Anchor – obviously, this is the business end. They come in all types, weights and sizes. Each type has strengths and weaknesses and may work better or worse depending on the bottom conditions. Most small yachts have a single primary anchor (and ideally a second anchor), so you need one that will work well in the widest range of conditions as possible.

Swivel / Shackle – This is how your chain actually connects to your anchor. This is another passionate-opinion topic. Swivels got a bad name because some designs do not tolerate the boat swinging and pulling on the anchor sideways. The Mantis Swivel is one that does not have this problem and is what we use. A swivel will prevent(or reduce) your chain from twisting up. That said, lots of boaters are perfectly happy with a plain old fashioned anchor shackle. Just get a good quality one – not this one

Rode: Chain/Rope

The bits between you and the bottom are normally some combination of chain and rope. The purpose of the chain is to provide weight to the rode so that the the rode stays at as low of an angle to the bottom as possible. Larger cruising boats will often have over 100 feet of chain followed by rope so that in most circumstances, the entire rode that is payed out will be chain. Smaller boats can usually get away with as little as 20 feet of chain followed by rope. Boats with a lot of chain generally will have a windlass which is an electric winch on the bow used for raising (weighing) or lowering the anchor.

Snubber and Chain Hook

Bigger boats with all chain will normally deploy some sort of snubber line. This consists of a length of pretty beefy rope with some sort of chain hook on the end. You will also often see this in a bridal setup where there are two lengths of rope with the chain hook in the middle. The rope end(s) then connect to cleats the same way a mooring line would. The idea of this setup, is that the snubber carries all the tension of the anchor rode instead of putting that constant load on the windlass. It also adds a bit more elasticity to the system as you would typically use three-strand nylon for the rope(s). We do a single 30 foot line of 3/4″ nylon with an eye splice to our chain hook. This is a seriously heavy-duty setup and has been stretched like a guitar string more than once!

Argon’s Chain Hook and snubber Line Closeup (L) and Deployed (R)

Important Chain Hook Feature – Picture this: it’s 0230, the wind is howling, rain is driving sideways, and a squall has spun you 180 degrees with gusts in the 30s. No fun—but it happens. Now imagine you need to fire up the engine and move quickly to avoid disaster—maybe you’re dragging, or swinging toward the shallows. The last thing you want in that moment is to wrestle your snubber off the chain! A well-designed hook will pop free automatically as it rolls over the bow roller. Our claw-style hook on Argon does exactly that—and it’s my favorite feature of our ground tackle.

Choose Your Bottom

Know where to anchor and where not to. The navionics app (and others) indicate anchoring areas – many with reviews from other skippers and detailed information. You want sand or mud. You do not want rocks, foul areas or heavy sea grass. In the Caribbean and Bahamas, we have the luxury of being able to see the bottom we’re anchoring in so it’s easy to find sand and avoid the rocks and grass. Here in New England, we drop, trust the chart data and hope for the best.

Choose Your Shelter

No anchorage is perfect in all conditions. Potters Cove is great in the normal southwest wind, but it’s the last place you would want to be in a NE wind. The land you are anchoring near is sheltering you from wind and waves. Know the wind forecast for the time you plan to anchor and choose accordingly.

Backing Down

One way or another, you want to make sure your anchor digs in well and is holding solid. If it’s windy enough, the boat will put a pretty good tug on it without any help. But it’s always good to apply a little reverse horsepower to really set the anchor. Pro tip: If you back down hard in light wind, be careful when you go back in neutral because you will tend to slingshot forward over your anchor. Usually not a problem, but beware. In those conditions, it’s better to slowly reduce the reverse thrust and gradually settle back to the normal tension on the chain.

Feel The Rode

We see lots of boaters drop the hook from a pushbutton in the cockpit and call it a day. We never like to see those folks upwind from us – especially overnight. When the anchor bites and you have let out nominally enough scope, hold onto the chain and feel it as you back down on the anchor. Is it locked in tight? Is it skipping over pebbles or shells? Is it dragging through soft mud? You will want that confidence at 3AM when you wake up and the wind is howling in the rigging.

Don’t Run Over Your Anchor

Here’s a classic we’ve seen over and over—boats dropping anchor while still moving forward at 2 knots or more. The boat keeps coasting two or three boat lengths forward, and when the anchor finally bites, it is way behind the boat and it swings the yacht stern-to-the-wind at first. With luck, the boat will fall back off the wind and eventually get into a good position. With less good luck, you end up with chain fouled around the keel, rudder or other underwater appendages.

What to do instead: As the boat slows, lower the anchor just to the surface and watch it. You’ll see how fast you’re still moving. Only drop it once you’ve come to a near or full stop. Ideally, the anchor hits the bottom just as you are starting to drift backward. Let the chain pay out gradually while moving very slowly in reverse..

Develop Hand Signals

When you have one person at the helm and another on the foredeck, yelling over the wind isn’t a great communication plan. That’s why we rely on hand signals. Yes, you can use headsets, but ick…. more gadgets to fail. Hand signals work great. note: these are the same we use for mooring maneuvers.

Make sure the crew agree on the signals before you anchor, and practice them. For us, the main vocabulary is:

- Fist Up – Forward propulsion

- Fist Down – Reverse propulsion

- Hand extended port/starboard – directional order

- The international tiny bit gesture of finger and thumb close together can be used to modify the propulsion orders to “just a little”.

- One hand above the other – “what is the depth?” Helmsman replies with finger digits (one finger then six fingers = 16 feet)

Scope

Scope is the ratio of how much rode you have to the water depth. Putting out 50 feet of rode out in 10 feet of water would be 5:1. The idea is to be pulling on the anchor as horizontally as possible. Ideally, the last bit of chain before the anchor never lifts off the bottom. The standard advice is to use a 5:1 – 7:1 scope. That’s a solid baseline but there are several factors that might affect that up or down. Those factors include, but are not limited to:

- How long you plan to stay

- Current and Expected Winds during your stay

- Bottom composition

- Rode composition (all chain = better set than partial chain + rope)

If you’re in soft mud, if there’s seagrass, if the bottom is rocky, or if high winds are forecast—adjust accordingly. We’ve used everything from 4:1 in tight anchorages with no wind to 10:1 when preparing for squalls. In extreme storm conditions, some yachts will put out a second anchor at 30-45 degrees off the primary.

How much chain did I put out? People come up with all sorts of tricks to mark their chain. Paint, Zip-ties, Little plastic things from West Marine. I think it’s worth it to mark your chain as a reference, but the easiest way to know how much chain is out is… time. Your windlass (if you have one) pays out chain at a pretty consistent rate. You can quickly figure out how much chain goes out in a given amount of time. On Argon. 10 seconds pays out about 20 feet. We get the first 40 feet out in 20 seconds (our old faded paint on the chain confirms this). Another 10 seconds gets us to 60 (where there is another mark) and so on. This technique works especially great at night. Just beware that when under stress, you will tend to count your seconds faster… relax and if in doubt, put out more.

Turn off the Windlass Breaker when Not In Use

It doesn’t happen often, but there are terrible stories about a windlass spontaneously spinning up or down (neither is ideal). Remember: your windlass up/down buttons are $0.39 microswitches which are exposed to salt water environments. A failure in that switch is all that is between you and a very bad day. We learned this in Nova Scotia. We were ready to drop the anchor. I pressed the DOWN button for second just to test it and… it stuck on and kept paying out! I learned then to not trust these switches at all. This also highlights the importance that all crew members know where the windlass breaker is.

Our routine is to energize the windlass breaker while approaching the anchorage and turn it off as soon as we’re set. When weighing the anchor, turning on that breaker is the last thing we do and then it is turned off as soon as we’re underway. This is an easy thing to get in the habit of and a really good idea.

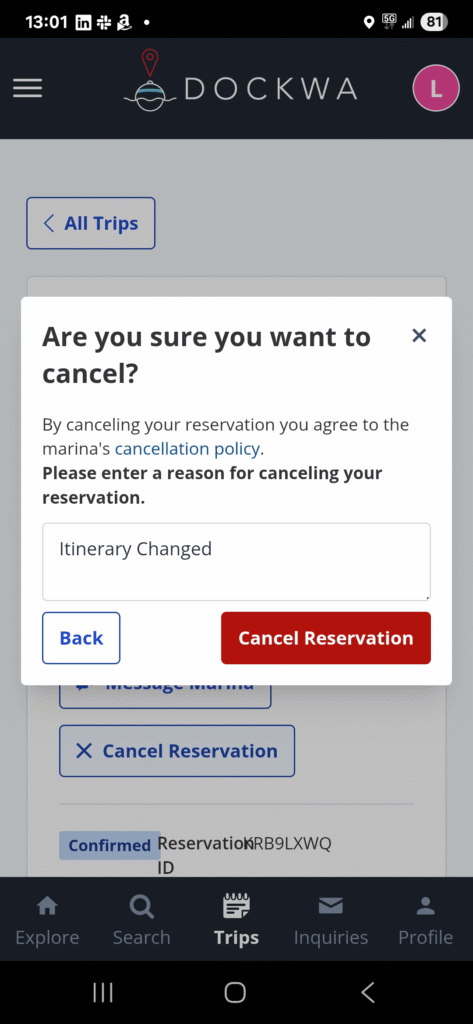

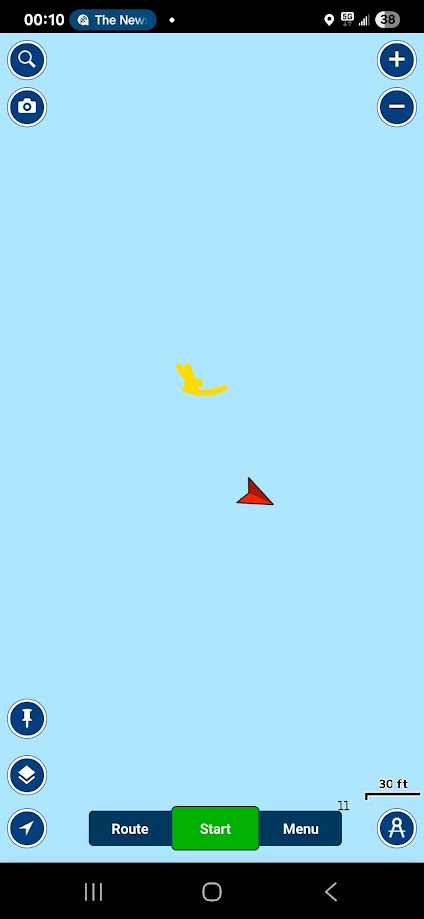

Use a Monitoring Method That Works for You

There are tons of apps out there for monitoring anchor position and triggering alarms if you drag. If that works for you, great—but you don’t need high-tech tools to anchor safely.

Here’s our low-tech method: After we set the anchor, we start recording a GPS track in Navionics on a phone or tablet left inside near the center of the boat. After 20 or so minutes, we stop the track. That leaves us with a “squiggle” showing the normal swing pattern of the boat at anchor.

Later, we can compare our current position to that squiggle. If all is well, we will either be on the squiggle or somewhere along an arc from the squiggle if the wind has shifted. This is a nice quick sanity check when you wake up in the middle of the night.

If the wind shifts significantly, we record a new squiggle and then monitor against that. We also generally set a waypoint on the main ship’s chartplotter where we drop the anchor.

If/When you drag. The typical advice is to put out more scope. That’s normally a good idea – if there is room (see Gray Poupon moment above). If another 10 or 20 feet fixes it, great. If not, it’s time to move and set the hook again. This can be particularly fun at 3AM in the driving rain. Normally if you drag, it’s very slow. This makes the monitoring solution important because it’s hard to notice until you’ve dragged a long way.

The Windlass Is for Lifting—Not Pulling

Windlasses are amazing tools, but they’re not meant to drag your boat forward. When weighing anchor, your boat should be moving slowly toward the anchor under its own power, and the windlass should simply be collecting chain. Here is where the hand signals come in handy again – signal to the helmsman to roll the boat forward such that you are pulling the chain straight up. When you get over your anchor, it will normally pop right off the bottom (unless you hook the poorly marked cable in Newport Harbor – ask me how I know).

Letting the windlass do all the work is tough on the motor and gearbox. It also risks tripping the breaker. Windlass breakers are normally thermal type breakers and once tripped, have to cool down for some time (it seems very long at the moment) until you can re-energize it. During that time, you are a bit vulnerable – either still hooked with very little scope, or worse with an anchor that pulls out but just skips over the bottom. If this happens, do not drive forward! If you need to get some way on to control the boat, reverse to keep the anchor out front of the boat.

Don’t slam the anchor back into the roller with the windlass. Do those last few inches by hand. We often hear the loud “clunk” when people are leaving.

Be Aware of Your Swing

Your boat will swing as the wind shifts—that’s a given. But how much it swings and whether you’ll stay put are major safety considerations.

Before you settle in for the night, check the wind forecast for the time you expect to be anchored. Will the wind clock around? Will it blow harder? In New England, summer squalls and thunderstorms often bring sudden 180s with strong gusts.

Below are some photos from a recent 1AM anchor watch. We anchored in SSW wind but overnight, the wind would turn to the NW. We set hourly alarms to check and here we are about halfway through the swing facing due west. You can see that compared to the original squggle, we’re at about 3 o’clock on the arc. The wind was light. We were fine. Just a little tired the next day is all.

If you expect a significant shift, maybe pay out a little extra scope. Your anchor dug in at 30°, but maybe at midnight, it will be more like 120°. If the wind is light, it’s probably just fine. If not, you might consider setting sleep alarms and getting up as it is shifting. We’ve spent many long nights taking turns on anchor watch. It’s not fun, but it’s part of the adventure.

Sailing at Anchor

You may hear the term Sailing At Anchor. This happens to some degree on all boats as the wind picks up. The bow gets slightly off the wind and because the boat has more windage now, it gets pushed more off the wind. Eventually, the stern comes around and lines you back up with the wind but then… the bow goes off the wind on the other side. Rinse and repeat. It is during these swings off the wind that your ground tackle is put under the most tension. Some boats will deploy a stabilizing sail at the stern. The idea of this is to keep the stern straight downwind so the sailing is minimized. They can work great at reducing those intermittent loads but the tradeoff is that you have slightly increased windage all the time.

Lights and Shapes

Turn on your anchor light before you head out to dinner if you’re returning late. Turn it off when you get your first coffee. If your anchor light does not work, you really need to put some sort of all-around white light or deck illumination on the boat. Do not turn on your running lights just to be “more visible”. Running lights mean you are underway and you are most definitely not underway if you are tied to the bottom of the ocean. Still, we see this quite often.

Technically, you should show the anchoring day shape of a single black ball. Very few people up north do this but we saw it a lot in the Caribbean. In a recent weekend anchoring in Block Island, there was only one of hundreds of anchored boats with the day shape. We heard a story recently (hearsay) that someone had a collision during the day while anchoring and his insurance company denied his claim because he was not showing the day shape. It’s $23 on Amazon and folds up small. Might not be a bad idea.

The Rolly Night

It happens – the wind is from the south, but the swell is from the west. Your boat has a rolling motion all night long. It’s as if someone is nudging you every 5 seconds saying “hey – wake up”. This can happen anywhere on windless nights where the boat will tend to sit side-to the swell. It can also happen after a wind shift when there are still many hours of swell from the old direction hitting you on the side. Some anchorages have swell that wraps around the opening of the harbor and hits you from the side.

What can you do? Some folks will put out a second stern anchor to orient the boat perpendicular to the swell. It works, but it’s a bit tricky to do – especially in the middle of the night. Personally, I don’t want any extra “complication” down there. A more low-tech solution is to try and find a way to sleep sideways in the boat. I’ve actually put a cockpit cushion at the foot of the companionway steps and slept behind the galley sink. Either way, you’re in for a bad night. You can always just move to a different anchorage too – or start early to your next destination with a lovely overnight sail.

Final Thoughts: A Peaceful Anchorage Starts with Good Habits

Good anchoring isn’t just about dropping the hook and hoping for the best—it’s about planning, communicating, and staying aware. The better your habits, the more peaceful your night will be. As New England Mooring and Docking becomes more and more expensive, adding anchoring to your options can save a lot of money while cruising. But simple mistakes can be costly too.

We’ve made mistakes along the way—everyone does—but with every season and every new anchorage, we’ve learned something new. That’s part of the joy of cruising.

Whether you’re spending a summer weekend on Narragansett Bay or cruising off Grenada, anchoring well is one of the most valuable seamanship skills you can have. Have you had your own anchoring adventure—or misadventure? Share it with us in the comments!”

Sleep well—and stay put.